Manuscript Study: Dante's The Divine Comedy

By

Susan M. Lee

San Jose State University

LIBR 280-12

March 4, 2013Dante's La Commedia (The Divine Comedy)

|

| Dante Monument in Piazza del Signori - Verona, Italy |

BACKGROUND

According to respected historian Robert Darnton, a book’s history is influenced as it passes from the author to the publisher, to the printer, to the shipper, to the bookseller, and finally to the reader. Book history “concerns each phase of this process and the process as a whole, in all its variations” and “economic, social, political, and cultural [systems] in the surrounding environment” (Darnton, 2006).

Dante di Alighieri degli Alighieri was very much a product of his environment. His character was formed by three major life events: The death of his first love Beatrice, his harsh exile, and the death of his dream of “an ideal empire which would do man’s business on earth while a reformed and no longer worldly papacy took care of heaven’s business” (Chubb, 1966). He was “shaped and educated by the doings of his energetic family” and “taught by the people whom he met or saw or heard about in Florence” (Chubb, 1966).

Although he was also a historian, philosopher, and theologian, Dante is most well-known for writing The Divine Comedy, an epic and dramatic allegory about the afterlife, consisting of three parts: the Inferno, the Purgatorio, and the Paradisio, or Hell, Purgatory and Heaven. Dante’s highly influential work was remarkable in that it was written entirely in Italian rather than Latin as other medieval writers were doing (Rizatti, 1965). It was also written in terza rim verse form. The Divine Comedy is famous for its rich and detailed illustrations of both Heaven and Hell but it also provided “a political and social history of the Italy in which Dante lived” (Rizatti, 1965). Dante includes “his own friends and enemies…along with great figures from the historical and legendary past” in The Divine Comedy (Rizatti, 1965). Thus, Dante’s work is both formed and informed by his surroundings.

Born into one of the city’s oldest Guelph families to Alighieri II and Gabriella (Chubb, 1966), Dante grew up in the hills of Florence, Italy during late Middle Ages, when the city was ruled by a German emperor (Rizatti, 1965), still “small, grim, unadorned” (Rizatti, 1965) and not the epicenter of trade and commerce it would soon become.

To a prideful Dante, Florence was “the fair sheephold where I slept as a lamb” -Paradiso Canto XXV.

The people valued simplicity, “living soberly and on coarse food… clad in rough garments” (Chubb, 1966). His family home was in a commune of San Martino del Vescovo (Chubb, 1966). Florence was filled with “practical people” and its churches “small, modest,” even Dante’s “bel San Giovanni,” the Baptistery was in a “rough, unfinished state” (Rizatti, 1965). Despite being forcibly banished from Florence in 1301 or risk the threat of death, the city remained one of Dante’s two greatest loves; the other being Beatrice, one of the central characters in The Divine Comedy (Rizatti, 1965).

Little remains of Dante’s life in terms of actual artifacts or facts aside from what one can discern from The Divine Comedy. Born in May of 1265, although the exact date is unknown, Dante’s aristocratic parents died when he was young (Rizatti, 1965). His mother came from the Berti family, who were more notable and respected than the Alighieri’s (Chubb, 1966). The family’s wealth came mostly from their businesses and land dealings (Chubb, 1966). Although Dante’s father was not the wealthiest of his extended family, he left his sons “a more than modest property” (Chubb, 1966). The family name and reputation dwindled as the old “aristocracy of blood gave way to aristocracy of money,” the bankers and merchants (Rizatti, 1965). In 1277, a twelve-year old Dante entered into an arranged marriage with a ten-year old Gemma Donati who came from a wealthy Italian family (Rizatti, 1965).They would later produce five children, Giovanni, Pietro, Jacopo, Antonia, and the youngest Beatrice (Rizatti, 1965). Dante developed a great love for music and writing verse (Rizatti, 1965).

Dante’s real-life muse Beatrice Portinari’s physical looks are a mystery (Rizatti, 1965). In Paradise, Beatrice has a pearl complexion. In Purgatoria, Beatrice has emerald eyes that shine with love; "See that you do not spare your eyes: we have set you in front of the bright emeralds, from which Love once shot his arrows at you.’ A thousand desires, hotter than flame, kept my eyes fixed on those shining eyes" - Purgatorio Canto XXXI: 91-145. He met and fell in love with her when he was just nine years old (Rizatti, 1965). The pair saw each other frequently but his pre-arranged marriage prevented their relationship from developing past the spiritual (Rizatti, 1965). After her death at the age of 25 in 1290, Dante continued to see her in an exatlted form during his visions; she speaks to him in “Purgatoria” alive and well, “maternal, radiant and comforting” (Rizatti, 1965).

Dante spent his days studying philosophy or in lecture hall, his nights were usually spent at the local tavern (Chubb, 1966). Forese Donati was one of Dante’s best friends in his youth. Donati, also his cousin through marriage, encouraged Dante’s youthful transgressions and follies (Rizatti, 1965). His other good friend Guido Cavalcanti, was a polar opposite – ten years older and a respected poet in the school of the New Style. Guido repeatedly implored Dante to give up his life of aimless pleasure and become more serious. By 1300, both Forese and Guido died, leaving Dante alone (Rizatti 1965).

Dante developed an interest in politics as well as the arts (Rizatti 1965). His political opinion became highly respected regarding affairs of the state (Chubb, 1966). Dante was a great fan of Virgil, a well-known and respected writer of antiquity (Rizatti, 36). In The Divine Comedy, Virgil is the “gentle leader” and “sage master” (Rizatti, 36), serving one of three guides who can lead man back to his earthly happiness (Rizatti, 35). The others are the aforementioned Beatrice and St. Bernard. Dante joined the Guild of Doctors and Druggists. Perhaps he saw the social benefits as his own family name lost its prominence and he then often relied on his wife’s family connections. Dante picked a good time to join as an intellectual, as the Major Arts, consisting of seven powerful guilds, grew in significance and political influence (Rizatti, 26). Dante became a member of the Priorate, or politician, in 1300 (Rizatti, 26). Although he was well-regarded, Dante’s outspokenness and unyielding will made him a great deal of enemies, including Pope Boniface VIII (Chubb, 1966). Dante continued to write poetry during this time; it was his custom to send every several cantos he wrote to Italian nobleman Can Grande (Chubb, 1966). Dante wrote to Can of his work “"to remove those living in this life from the state of misery and lead them to the state of felicity” (Chubb, 1966). Anyone could then make a copy of the manuscript after Can Grande had finished reading it (Chubb, 1966).

An international and political feud between Italy and Tuscany developed during Dante’s life in Florence, in the form of the Guelphs, supporters of royal house of Bavaria, and the Ghibellines, supporters of royal house of Swabia as both grappled for control of the old Roman Empire (Rizatti, 1965).Others caught in the middle were often driven by other motivations like personal and familial grudges (Rizatti, 1965). Thousands were killed. Dante describes the slaughter in The Divine Comedy when he wrote “The great slaughter and havoc that dyed the Arbia red, is the cause of those indictments against them, in our churches” (Inferno Canto X: 73-93).

A 24-year old Dante witnessed similar violent and bloody battles during the summer of 1289 as a soldier during the battle of Campaldino and the siege of the fortress of Caprona as he fought for the Guelph side (Rizatti, 1965). His experiences fleeing from the enemy would haunt him later in his work, specifically Inferno (Rizatti, 1965). Although the Guelphs would emerge victorious, their triumph was short-lived. The next battle for control was within the Guelphs, between the Whites (bourgeois merchants, bankers, and manufacturers) and the Blacks (the descendants of the ancient feudal aristocracy and proletariat (Rizatti, 1965). Florence was again divided in violent conflict which erupted two months after Dante joined the Priorate (Rizatti, 1965). To diffuse the fighting, the Priors, including Dante, voted to banish the leaders of the Whites and the Blacks but it only resulted in more anger and unrest within the city (Rizatti, 1965). Power was returned to the Blacks by Charles de Valois, on behalf of Pope Boniface VIII (Rizatti, 1965). The Blacks embarked on a path of destroying their opponents. Dante was a devout Christian who believed that the Church would guide you through the authority of Scripture (Rizatti, 1965). Dante disliked and opposed Boniface VIII for a variety of reasons. The biggest was the Pope’s strong belief in the temporal sword whereas Dante believed in the separation of Church and politics (Rizatti, 1965).

Dante and his family were given a sentence of banishment and exile (Rizatti, 1965). Although Dante’s fervent hope was that Luxembourg Prince and Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII would restore Florence to its former glory when he entered Italy in 1310 with his army, and unban Dante from exile (Rizatti, 1965). Dante’s hope died with Henry VII, when the emperor caught malaria and died, yet Dante’s faith lingered, reflected in his writing (Rizatti, 1965). Perhaps he was stuck on what could have been. The exact dates are not known but he began writing Inferno sometime before 1301 and finished it within 20 years (Chubb, 1966).

After his forced exile, Dante wandered the country until his death in 1302 (Rizatti, 1965). It was during this time that he wrote the bulk of The Divine Comedy (Chubb, 1966). The first several cantos were found after his exile (Chubb, 1966). The last thirteen cantos were found after his death (Chubb, 1966). Dante spent time in Paris, Verona and Ravenna but he never settled down or put roots anywhere, always hoping to be welcomed back into his birthplace (Rizatti, 1965). Life was hard for him; neither his name nor his artistic talent held value. There were no wealthy patrons or benefactors of the arts yet so Dante worked as a secretary and diplomat (Rigatti 70). He also taught poetry in the vulgar tongue (Chubb, 1966). He was the first to make it popular and respected among Italians. Until then, it had only been used for the “lightest sort of love trifles” (Chubb, 1966).

The Divine Comedy worked for Dante in another way; warlords took Dante under their wing due to his newfound reputation as a sorcerer, “an expert in the realms beyond the grave” (Rizatti, 1965).

As a medieval poet, Dante served as both educator and publicist, injecting his writing with an infusion of symbolism (Rizatti, 1965). The Divine Comedy “can be read allegorically, as the itinerary of mankind in search of blessedness (Rizatti, 1965). It depicted Dante’s journey through hell and purgatory and paradise until he encounters God, having been guided by favored Latin poet Virgil. To appeal to the reader, Dante uses recognizable symbols like Gods and monsters “to make abstract concepts of peace and justice, redemption and happiness” and characters like Beatrice “personifies grace and theology” (Rizatti, 1965). His journey through darkness towards spiritual awakening still speaks to us today.

Surrounded by his children and other loved ones, Dante died at the age of 56 years old in the summer of 1321 from malaria after returning to tranquil Ravenna from a diplomatic mission in Venice (Rizatti, 1965). He was buried in the Church of St. Francis with full honors (Rizatti, 1965).

No historically accurate depiction of Dante exists, or at least acknowledged but these are two of the earliest ones:

credit: World of Dante Gallery: http://www.worldofdante.org/gallery_dante_portraits.html

Introduction to The Divine Comedy

"Dante's is a visual imagination" - T.S. Eliot

The Divine Comedy inspired many artistic manuscript illuminations during the Middle Ages and a variety of depictions in other media in the present day.

Link to digital manuscript: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Yates_Thompson_MS_36

The Yates Thompson is one of the finest Italian illuminated manuscripts. The codex was produced during the middle 15th century. Each illumination is surrounded by an ornamental border which varies in design consisting of regular miniature. Priamo della Quercia completed the illuminations for the Inferno and Purgatorio and all three historiated initials, Giovanni di Paolo completed the illuminations for Paradiso (Credit: http://www.worldofdante.org/gallery_yates_thompson.html)

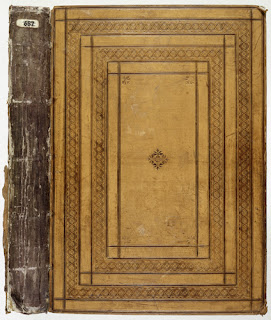

Front binding:

Rear Binding

Inferno

excerpt:

Canto II

Day was departing, and the embrowned air

Released the animals that are on earth

From their fatigues; and I the only one

Made myself ready to sustain the war,

Both of the way and likewise of the woe,

Which memory that errs not shall retrace.

O Muses, O high genius, now assist me!

O memory, that didst write down what I saw,

Here thy nobility shall be manifest!

| ||

| 4.88 Limbo - Dante and Virgil with Ovid, Homer, Lucan, and Horace; the castle of Limbo by della Quercia |

Purgatory

excerpt:

Canto VIII

'Twas now the hour that turneth back desire

In those who sail the sea, and melts the heart,

The day they've said to their sweet friends farewell,

And the new pilgrim penetrates with love,

If he doth hear from far away a bell

That seemeth to deplore the dying day,

When I began to make of no avail

My hearing, and to watch one of the souls

Uprisen, that begged attention with its hand.

Paradise

Excerpt:

Canto XXI

Already on my Lady's face mine eyes

Again were fastened, and with these my mind,

And from all other purpose was withdrawn;

And she smiled not; but "If I were to smile,"

She unto me began, "thou wouldst become

Like Semele, when she was turned to ashes.

Because my beauty, that along the stairs

Of the eternal palace more enkindles,

As thou hast seen, the farther we ascend,

Photos of the Manuscript:

Divina Commedia Manuscript information:

Incipit - Inferno. Incipit (f. 1r): 'Nel mezo del camin di nostra vita / mi ritrovai per una selva scura'. 2. (ff. 65r-128r): Purgatorio. Incipit (f. 65r): 'Per corre meglior acqua alza le vele / omai la navjcella dell'. Incipit (f. 129r): '[L]a gloria de chului che tuctu move / per luniverso penetre risplende'.

Explicit - n/a

Colophon - This manuscript does not contain this element. It not usually found in manuscripts like this, believed to be dated 1444.

Language - Italian, the author's native tongue.

Size - 365 x 258 mm (text space: 215 x 80 mm)

Binding - The parchment papers are placed in a Post-1600 tooled brown leather binding with gilt edged leaves and marbled endpapers.

Material written on - Parchment paper. Many medieval manuscripts were written on parchment (or sometimes called vellum paper), made from lime-solution treated animal skin which was then scrapped with a knife after the fur was removed and stretched out. The process was repeated, often several times, until the paper was as thin as needed.

Foliation - ff. 190 + iii (+ 3 unfoliated modern paper flyleaves: 1 at the beginning and 3 at the end; ff. i-ii are modern paper flyleaves with modern notes on provenance; f. iii is a parchment flyleaf before f. 1)

Collation - Mostly in quires of 8: i-xix8 (ff. 1-152), xx6 (ff. 153-158), xxi-xxiv8 (ff. 159-190)

Script - Gothic

Hands of different scribes -Copiato da una sola mano (copied from a single hand)

Ink -unsure but best guess, iron-gall or oak-gall since parchment paper was used. Typically, the parchment paper was ruled with leadpoint or colored ink and then written on with quill pen. You can see colored ink in the above manuscript.

Rubrication - 3. (ff. 129r-190v): Paradiso. Rubric (in gold, f. 129r): '[C]omincia la terza cantica di la comedia di dante aldighieri de firenze chiamata paradiso nella quale tracta de beati e dilla celestiale gloria e di meriti e premij di santi e dividise in nove parti si come lo inferno canto primo nello cui principio lautore prohemiza alla sequente cantica e sono nello alimento dill o fuogo e Beatrice solue allo autore una questione nello quale canto lautore promecte di tractare le cose divine invocando la sicentia poetica cioe apollo idio dilla sapientia'.

Decoration - 3 large historiated initials, developing partial foliate borders, in colours and gold, at the beginning of the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso (ff. 1r, 65r, 129r). 110 large miniatures in the lower margin, in colours and gold (ff. 2r, 4r, 5r, 6r, 7v, 8v, 9r, 10r, 11r, 12v, 14r, 16r, 18r, 20r, 21v, 23r, 25r, 27r, 29r, 30v, 32r, 34r, 35v, 37v, 39v, 42r, 44r, 46r, 47v, 49r, 51r, 53r, 55r, 56v, 59r, 61r, 62v, 68r, 76v, 84r, 88r, 93v, 98v, 100r, 107r, 113v, 116v, 119r, 129r, 130r, 131r, 132r, 133r, 134r, 135r, 136r, 137r, 138r, 139r, 140r, 141r, 142r, 143r, 144r, 145r, 146r, 147r, 148r, 149r, 150r, 151r, 152r, 153r, 154r, 155r, 156r, 157r, 158r, 159r, 160r, 161r, 162r, 163r, 164r, 165r, 166r, 167r, 168r, 169r, 170r, 171r, 172r, 173r, 174r, 175r, 176r, 177r, 178r, 179r, 180r, 181r, 182r, 183r, 184r, 185r, 186r, 187r, 188r, 189r, 190r). Large decorated initials with foliate extensions into the margins, in colours and gold. Small initials in gold on pink, blue, and/or green grounds.

Illumination/Painting - From Latin, illuminare, "to light up or illuminate," The images in handwritten manuscripts are called illuminations because of the glow created by the gold, silver, and other colors. The ones in the Yates Thompson 36 were done by Priamo della Quercia and Giovanni di Paolo as noted above. Typically, the artist draws an outline with leadpoint or ink, paints the areas to be painted with bole, or gum ammoniac. Gold leaf was then laid down first and rubbed onto the paper to make the paper shine. The artist then paints their picture with a variety of "ground minerals, organic dyes extracted from plants, and chemically produced colorants," usually mixed with the whites of egg to create tempera paint. What is interesting is that the 19th century brought newfound interest in the Middle Ages, also called Gothic Revival, with particular interest in the artistry of manuscripts from that time. Forgeries of manuscripts began to pop up. One common inaccuracy spottable in forgeries is the golf leaf laid down last, not first.

The images in the Yates Thompson 36 manuscript appear mostly intact. During the 1800s, collectors and thieves would cut out illuminations from manuscripts. Some were legally aquired but others were stolen from even from library collections. They would then be framed or added to private collections of artwork, devaluing and vandalizing the original manuscripts.

3 large historiated initials, developing partial foliate borders, in colours and gold, at the beginning of the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso (ff. 1, 65, 129). 110 large miniatures in the lower margin, in colours and gold (ff. 2, 4, 5, 6, 7v, 8v, 9, 10, 11, 12v, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21v, 23, 25, 27, 29, 30v, 32, 34, 35v, 37v, 39v, 42, 44, 46, 47v, 49, 51, 53, 55, 56v, 59, 61, 62v, 68, 76v, 84, 88, 93v, 98v, 100, 107, 113v, 116v, 119, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190). Large decorated initials with foliate extensions into the margins, in colours and gold. Small initials in gold on pink, blue, and/or green grounds.

The images in the Yates Thompson 36 manuscript appear mostly intact. During the 1800s, collectors and thieves would cut out illuminations from manuscripts. Some were legally aquired but others were stolen from even from library collections. They would then be framed or added to private collections of artwork, devaluing and vandalizing the original manuscripts.

3 large historiated initials, developing partial foliate borders, in colours and gold, at the beginning of the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso (ff. 1, 65, 129). 110 large miniatures in the lower margin, in colours and gold (ff. 2, 4, 5, 6, 7v, 8v, 9, 10, 11, 12v, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21v, 23, 25, 27, 29, 30v, 32, 34, 35v, 37v, 39v, 42, 44, 46, 47v, 49, 51, 53, 55, 56v, 59, 61, 62v, 68, 76v, 84, 88, 93v, 98v, 100, 107, 113v, 116v, 119, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190). Large decorated initials with foliate extensions into the margins, in colours and gold. Small initials in gold on pink, blue, and/or green grounds.

Provenance/Ownership history - Unclear who commissioned the piece. History began with Alfonso V, king of Aragon, Naples and Sicily (reigned 1416 to 1458): his arms (f. 1r). Ferdinand (Fernando de Aragón), Duke of Calabria (b. 1488, d. 1550): his donation to the convent of San Miguel, Valencia in 1538. The monastery of San Miguel de los Reyes, Valencia, 1613: inscribed 'Ex commissione dominorum Inquisitorum Valentie vidi et expurgavi secundum expurgatorium novum Madriti 1612. et subscripsi die. 14. Septembris 1613. ego frater Antonius Oller' (f. 190v). Bought by Henry Yates Thompson from Señor Luis Mayans, Madrid, May 1901. Henry Yates Thompson (b. 1838, d. 1928), collector of illuminated manuscripts and newspaper proprietor: with his book-plate inscribed '[MS] CV / £blee.e.e [i.e. £1900.0.0] / [bought from] Harris / Madrid / May 29 / 1901' (inside upper cover). Bequeathed to the British Museum in 1941 by Mrs Yates Thompson

credit:

British Library Digitized Manuscripts http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Yates_Thompson_MS_36

Getty Library, The Making of a Medieval Book http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/making/

Collecting and transforming Medieval manuscripts http://www.finebooksmagazine.com/press/2012/12/collecting-and-transforming-medieval-manuscripts-at-the-getty.phtml

References -

Alighieri, Dante. (2006). The Divine Comedy. London: Dodo Press.

Rizatti, M. L. (1965). The Life & Times of Dante. Philadelphia: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore & The Curtis Publishing Company.

Alighieri, Dante. (2006). The Divine Comedy. London: Dodo Press.

Chubb, T. C. (1966). Dante and his world. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Darnton, R. (2006). What is the history of books? D. Finkelstein (Ed.), The Book History Reader (9-20) New York City: Routledge.

Rizatti, M. L. (1965). The Life & Times of Dante. Philadelphia: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore & The Curtis Publishing Company.

No comments:

Post a Comment